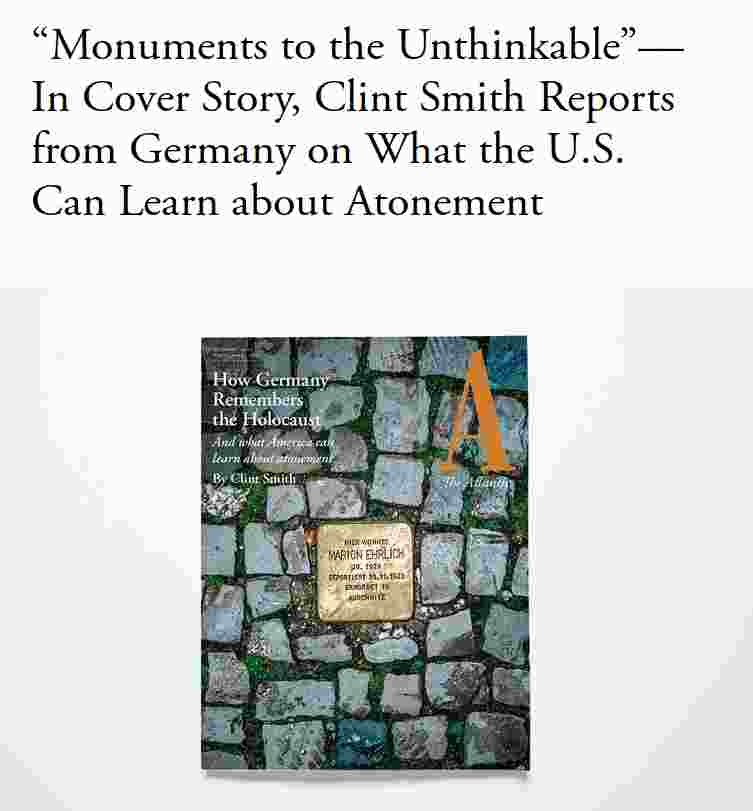

Headlining article in this month’s The Atlantic: The Stolpersteine

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/12/holocaust-remembrance-lessons-america/671893/

The first time I saw a Stolperstein, I almost walked past without noticing. I was heading back to my hotel after getting some tea at a café, and there they were, two of them. Small, golden cubes laid into a cobblestone sidewalk. They sat adjacent to each other outside what looked like an office building, or maybe a bank. I stepped closer to read what was written on each of them:

HIER WOHNTE

HELMUT HIMPEL

JG. 1907

IM WIDERSTAND

VERHAFTET 17.9.42

HINGERICHTET 13.5.1943

BERLIN-PLÖTZENSEE

HIER WOHNTE

MARIA TERWIEL

JG. 1910

IM WIDERSTAND

VERHAFTET 17.9.42

HINGERICHTET 5.8.1943

BERLIN-PLÖTZENSEE

Hier wohnte … Here lived …

The English translation for Stolperstein is “stumbling stone.” Each 10-by-10-centimeter concrete block is covered in a brass plate, with engravings that memorialize someone who was a victim of the Nazis between 1933 and 1945. The name, birthdate, and fate of each person are inscribed, and the stones are typically placed in front of their final residence. Most of the Stolpersteine commemorate the lives of Jewish people, but some are dedicated to Sinti and Roma, disabled people, gay people, and other victims of the Holocaust.

In 1996, the German artist Gunter Demnig, whose father fought for Nazi Germany in the war, began illegally placing these stones into the sidewalk of a neighborhood in Berlin. Initially, Demnig’s installations received little attention. But after a few months, when authorities discovered the small memorials, they deemed them an obstacle to construction work and attempted to get them removed. The workers tasked with pulling them out refused.

In 2000, Demnig’s Stolperstein installations began to be officially sanctioned by local governments. Today, more than 90,000 stumbling stones have been set into the streets and sidewalks of 30 European countries. Together, they make up the largest decentralized memorial in the world.

Demnig, now 75, spends much of his time on the road, personally installing most of the stones. Since 2005, the sculptor Michael Friedrichs-Friedländer has made the stones. Mass-manufacturing them would feel akin to the mechanized way that the Nazis killed so many millions of people, Demnig and Friedrichs-Friedländer say, so each one is engraved by hand.

I felt drawn to the Stolpersteine, compelled by the work Demnig was trying to do with them, and overwhelmed by how much they captured in such a small space.

The next day I met Barbara Steiner in the city’s Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district. The neighborhood’s narrow streets were lined with five- and six-story buildings whose balconies stretched out over the cobblestone sidewalks. People bundled in coats whizzed past us on bicycles.

Steiner, a convert to Judaism, is a historian and therapist. She has short, jet-black hair. She wore a sky-blue coat and small gold earrings that gleamed when they caught the sun.

“I have a 12-year-old daughter,” Steiner told me as we walked toward a Stolperstein a few meters away, “and whenever we walk in the streets, we stop.” She looked down at the engraved brass in front of us. “She really wants to read every stone.”

2 photos: woman in black dress and blue coat standing on cobblestone street; looking down on 4 brass memorial stones placed in cobblestone street with fall leaves

Left: Barbara Steiner in Berlin. Right: The German artist Gunter Demnig’s Stolpersteine memorialize victims of the Nazis. (Marc Wilson for The Atlantic)

“They mean more than those huge things,” Steiner said, stretching her arms wide above her head. “I think the huge monuments are always about performing memory, when this is really connected to a person.” Steiner likes that you see the names of specific people. She likes that the stones are installed directly in front of the place these individuals once called home. “You can start to think, How would it have looked for them to live here? ”

Stolpersteine are largely local initiatives, laid because a family, or residents of an apartment complex or neighborhood, got together and decided they wanted to commemorate the people who had once lived there. Steiner said that students at her daughter’s school had begun researching the building across the street from the school, and discovered that a number of Jewish families had lived there. Then they applied to have Stolpersteine installed.

Demnig has said that this is the most meaningful aspect of the project for him. He believes that for children and adults alike, 6 million is too abstract a number, and individual stories are more powerful tools than statistics for coming to terms with this history. “Sometimes you need just one fate,” he has said, to start thinking about how someone’s life relates to your own: Maybe they lived on your street, or were the same age you are now when they were murdered. “Those are the moments I know they will go home as different people.” Each stone creates its own unofficial ambassadors of memory.

Steiner and I walked a bit farther down the street. She stopped in front of a beige building with a large white archway above a brown door. “I lived here,” she said. I looked at the door, then looked down. Five stumbling stones lay together among the cobblestones, their brass faces shimmering. Steiner translated them into English for me:

Max Zuttermann. Born 1868.

Deported October 18, 1941.

Murdered January 15, 1942.

Gertrud Zuttermann. Born 1876.

Deported October 18, 1941.

Murdered December 20, 1941.

Fritz Hirschfeldt. Born 1902.

Deported October 18, 1941.

Murdered May 8, 1942.

Else Noah. Born 1873.

Deported July 17, 1942.

Murdered March 14, 1944.

Frieda Loewy. Born 1889.

humiliated/disenfranchised.

Died by suicide June 2, 1942.

I did the math to estimate how old they might have been when they died: Max Zuttermann, 74. Gertrud Zuttermann, 65. Fritz Hirschfeldt, 40. Else Noah, 71. Frieda Loewy, 53.

I glanced at Steiner; she was still looking down at the stones, her hands in her coat pockets, her legs crossed at her ankles.

I thought about what it must be like to live in a home where you walk past these stones, and these names, every day. I imagined what it might be like if we had something commensurate in the United States. If, in front of homes, restaurants, office buildings, churches, and schools there were stones to mark where and when enslaved people had been held, sold, killed. I shared this thought with Steiner. “The streets would be packed,” she said.

She was right. I imagined New Orleans, my hometown, once the busiest slave market in the country, and how entire streets would be covered in brass stones—whole neighborhoods paved with reminders of what had happened. New Orleans is, today, at a very different place in its reckoning with the past; it has only recently been focused on removing its homages to enslavers. Over the past few years, the statues of Confederate leaders I grew up seeing have been removed from their pedestals, and streets named after slaveholders have been renamed for local Black artists and intellectuals. My own middle school has a new name as well. As I looked at the stumbling stones beneath me in Berlin, I wondered if there might be a future for them on the streets I rode my bike on growing up.

I asked Steiner how it felt to have these stones here, in front of what was once her home. “My daughter now reads these names and asks herself, Could this be me? ” she said. “But what I like is to stand here and think about them, how they might have lived here.”

More Jewish people live in Boston than in all of Germany.

As I looked at the house, I began to imagine who these people could have been. Perhaps Max and Gertrud were married; I pictured them making Shabbat dinner for their adult children on Friday evenings. Perhaps Fritz helped them with their groceries as they made their way up the stairs. Maybe they spoke about what the Zuttermanns planned on cooking, whether they would see one another at synagogue on Saturday. Perhaps Max and Gertrud invited Fritz to join them for their meal. Perhaps they invited Else and Frieda too. Maybe they all sat around the table. Perhaps they laughed. Perhaps they sang. Perhaps they played a game of cards to end the evening. Perhaps, as wax began to collect at the bottom of the small plates that held the candles, they discussed the new laws that were restricting their lives, the rumors of war. Perhaps they asked one another whether they still had time to leave. (I later learned that Max and Gertrud were in fact married, and that Fritz was their subtenant. The Zuttermanns’ two adult daughters, I found, had been able to escape Germany.)

My eyes moved from the building we stood in front of to the buildings adjacent to it. When German Jews were led to the trains for deportation, the block would have been lined with other Germans who watched from their windows, their storefronts, the sidewalk. Maybe some cheered. Most probably said nothing.

Steiner saw me looking at these other buildings and must have realized what I was thinking about. “There’s the relational aspect,” she said. “It was their neighbors that had been murdered. It was their neighbors that had been deported. It was their neighbors that had been thrown out to Auschwitz. It was their neighbors who lost their lives. And we need to understand this. It was not an abstract group.”

So many of Germany’s monuments, I was learning, were not built until long after the war. The first Stolperstein was laid in 1996. The Gleis 17 memorial opened in 1998. The Jewish Museum Berlin opened in 2001. The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, in Berlin, opened in 2005.

When Steiner was a child, the country’s major sites of memory about the Holocaust were the concentration camps. Her parents had taken her to Dachau when she was very young. She was left haunted and terrified by the experience.

I asked if she had taken her daughter to any camps. She shook her head and told me she thought that, at 12, she was still too young. They had considered going to Auschwitz in the summer, but Steiner had changed her mind, ultimately deciding it wasn’t yet time. Her daughter had read about the Holocaust, and it seemed to have overwhelmed her. She struggled to sleep. “She was worried that if she fell asleep, she might not wake up,” Steiner told me.

Anti-Semitism and racism have been on the rise in Germany in recent years as the right-wing populist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has gained political power; the German government recently reported a 29 percent increase in anti-Semitic crimes. Steiner shared a story about how, on one recent Holocaust Memorial Day, two boys at her daughter’s school had pretended to “hunt” her daughter as they chased her through the hallways.

“She was … hunted by them?” I asked, wanting to make sure I had heard correctly.

“Yes, she was hunted by them.” Then, in a singsongy voice meant to emulate the melody of a nursery rhyme, she said what the boys had said to her daughter: “My grandfather was Adolf Hitler and he killed your grandfather.”

I put my hands in my pockets and took a deep breath.

“This is everyday Jewish life for children,” she said. “If you raise a Jewish child, how can you avoid this topic?”

Steiner’s question echoed the question that Black parents in the U.S. wrestle with every day. How can we protect our children from the stories of violence that they might find deeply upsetting while also giving them the history to understand who they are in relation to the world that surrounds them? My son is 5 years old; my daughter is 3. I think about what it means to strike that balance all the time.

I mentioned this to Steiner and she nodded, then looked back down at the stones in front of us. “I wonder what it’s like, because when you’re Black in America, at least there are more of you who could connect and support each other. There are so few Jews.”

This point—this difference—had become clear to me in my first few days in Germany. In the United States there are 41 million Black people; we make up 12.5 percent of the population. In Germany, there are approximately 120,000 Jewish people, out of a population of more than 80 million. They represent less than a quarter of 1 percent of the population. More Jewish people live in Boston than in all of Germany. (Today, many Jews in Germany are immigrants from the former Soviet Union and their descendants.) Lots of Germans do not personally know a Jewish person.

This is part of the reason, Steiner believes, that Germany is able to make Holocaust remembrance a prominent part of national life; Jewish people are a historical abstraction more than they are actual people. In the United States, there are still millions of Black people. You cannot simply build some monuments, lay down some wreaths each year, and apologize for what happened without seeing the manifestation of those past actions in the inequality between Black and white people all around you.

Steiner also believes that the small number of Jewish people who do reside in Germany exist in the collective imagination less as people, and more as empty canvases upon which Germans can paint their repentance. As the scholar James E. Young, the author of The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning, writes, “The initial impulse to memorialize events like the Holocaust may actually spring from an opposite and equal desire to forget them.” The American Jewish writer Dara Horn puts it more bluntly in her book People Love Dead Jews, writing that in our contemporary world, most people

only encountered dead Jews: people whose sole attribute was that they had been murdered, and whose murders served a clear purpose, which was to teach us something. Jews were people who, for moral and educational purposes, were supposed to be dead.

Steiner and I continued walking. Before, I had seen stumbling stones only intermittently; now I saw them in front of almost every building. Three here. Six there. Eight here. Twelve there. When we encountered a group of a dozen or more stones, we would stop, look down, and read the names as we had done in front of her old home. I saw dates of birth that read 1938, 1940, 1941. These were children—a 5-year-old, a 4-year-old, a 2-year-old.

A blackbird landed near the brass plates, jabbing its beak into the spaces between the cobblestones with quick, jerking movements. A little girl walked by and pointed in its direction, turning and saying something to her mother as she held her hand.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, recognized as the official Holocaust memorial of Germany, sits in the center of downtown Berlin, just south of the famous Brandenburg Gate and a block away from the site of the bunker where Hitler died by suicide. Designed by the American Jewish architect Peter Eisenman and spanning 200,000 square feet, it consists of rows of 2,711 concrete blocks that range in height from eight inches to more than 15 feet tall. The space resembles a graveyard, a vast cascade of stone markers with no names or engravings on their facade. The ground beneath them dips and rises like waves.

The memorial is significant not only for its size and location—the equivalent, in the United States, would be the placement of thousands of stone blocks in Lower Manhattan to honor those subjected to chattel slavery, or on Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C., to remember the victims of Indigenous genocide—but also because it was constructed with the political support and full financial backing of the German government.

Were these monuments built for Germans to collectively remember what had been done, or a performance of contrition for the rest of the world?

Steiner told me that, in her opinion, the stumbling stones are a much better means of memorialization than something like the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. “This has more to do with the German society and the expectation of having something big,” she said, stretching her hands out again. “We did a big Holocaust, we have a big monument.”

Steiner said that whenever she went down to the memorial, she saw people smoking while standing on top of the columns, or jumping back and forth from one to another. “It’s lost its purpose and meaning,” she said. “Maybe it never got it.”

When I visited the memorial, the sky was overcast, its long sweep of endless gray matching the color of the stone columns beneath it. A group of young people took selfies in front of the columns, some throwing up peace signs or puckering their lips as they sat cross-legged on top of a stone. Two women stood in between the shadows, their faces covered in tears, and held each other’s hands. A class of students looked up at their teacher as he explained what lay behind him, their eyes moving from him to the columns to one another with a silent solemnity. Three small children played hide-and-seek among the columns, shrieking in delight when they discovered one another. The memorial had become a part of the city’s landscape; different people engaged with the space in different ways.

photo of stair-stepped concrete columns against trees and sky